Most bizarre and weirdly sweet romantic comedy you’ll ever see and never forget, on Prime Video

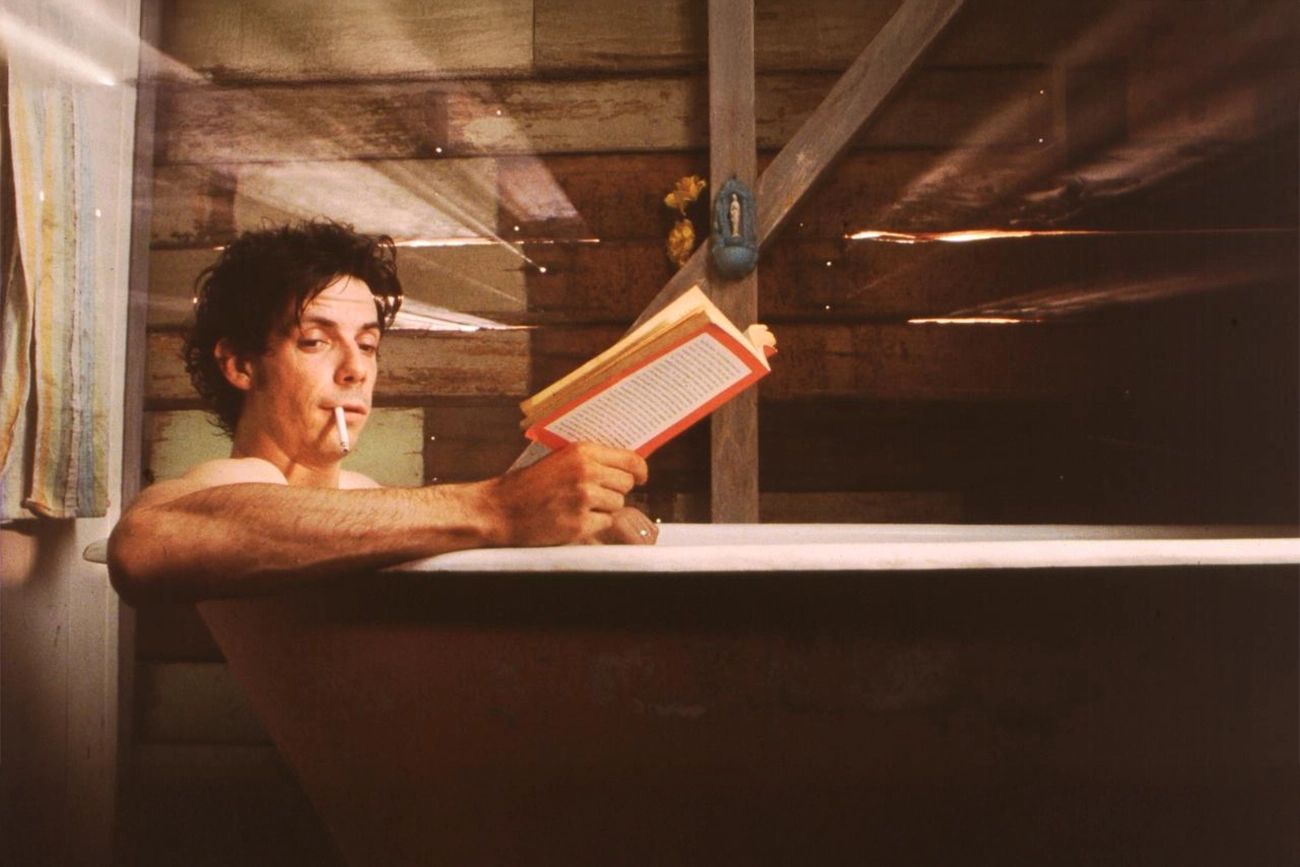

“He Died With a Falafel in His Hand” bursts onto the screen like a messy chronicle of urban youth, the kind that never admits discipline, but still reveals its own method: going through the chaos until it makes some sense. The first image of Danny, played by Noah Taylor, already suggests someone used to living with collapse, almost comfortable within it. The character carries an early tiredness, the kind of exhaustion that only those who have abandoned any fantasy of stability are capable of recognizing. Instead of a round arc, the film chooses to follow this boy as he traverses boarding houses, dormitories and apartments that function like small failed democracies: everyone talks too much, no one really listens, and yet the relationships tangle as if they were inevitable.

The entry of Sam, played by Emily Hamilton, injects another texture into this journey. She does not arrive as the optimistic breath that so many narratives impose on the female figure; appears more like someone trying not to get lost in their own youth. The way he observes Danny, sometimes with curiosity, sometimes with a certain involuntary compassion, reveals a sensitivity that is not at all naive, but has not yet learned to protect itself from the world. The dynamic between the two avoids easy romances and prefers to leave space for ambiguities that echo real experiences: a closeness that sometimes strays into affection, sometimes into discomfort, and often into something that escapes any objective classification.

The film gains momentum when Romane Bohringer enters the scene with an almost ritualistic energy. Her character, the pagan who takes her cults as seriously as she takes the urgency to provoke those around her, transforms each environment into unpredictable territory. It doesn’t matter if she’s staging a sacrificial bonfire or just watching the group with a smile like someone who knows more than she’s letting on; his presence reorganizes the narrative and forces Danny to grapple with perspectives he would rather ignore. There is something fun about this constant clash between adults who seem to compete over who can be more eccentric, and, paradoxically, the film finds sincerity exactly where eccentricity reaches the limit of absurdity.

Alex Minglet emerges as the figure who most accurately exposes everyday ridiculousness: the guy who drinks too much, fantasizes about non-existent guerrillas and turns a game of golf with frogs into an epic event. Comicity arises from the complete lack of proportion between your intentions and reality, and the result is irresistible. Haskel Daniel, as the TV devotee known as Jabber the Hut, composes a hilarious portrait of addiction to cheap distractions. Francis McMahon, in the role of Dirk, goes against the group when trying to reorganize his own identity, stumbling over the fear of saying what he feels. The fleeting appearance of the European who repeats the same phrase with misplaced conviction reinforces that this universe functions as a showcase of slightly misaligned existences.

When Brett Stewart brings Flip to life, the friend consumed by heroin, the narrative finds an indispensable point of gravity. The character’s physical degradation, visible in each new scene, breaks any expectation of total comedy and prevents the film from becoming just a succession of strangeness. Flip carries, without moralistic speeches, the reminder that some deviations are not picturesque; are devastating. It is exactly this combination of irony, melancholy and disenchanted humor that sustains much of the story’s emotional impact.

Danny’s journey through 49 houses, filled with people who would hardly share the same table in a more organized world, works as a metaphor for a youth that hasn’t found its axis, but isn’t interested in pretending to have found it either. Each change of address repeats the same pattern: the hope of starting from scratch, followed by the inevitable collapse that has always accompanied it. At a certain point, the accumulation of failures transforms physical displacement into internal movement. Danny begins to understand that it is not enough to escape from spaces; you need to reorganize the terrain within yourself.

The charm of the film lies precisely in the fact that it does not create a rigid plot. Instead, he prefers to collect encounters, cultural clashes, improvised rituals and minor breakdowns. When everything converges to an unexpectedly tender outcome, the impression arises that Danny has found a silver lining in the future. Not a monumental future or full of lessons, but the possibility, even if minimal, of moving forward without dragging the previous ruins.

The result is a sharp portrait of urban coexistence, where laughter never erases discomfort and tragedy never eliminates humor. A story that, beneath all its apparent disorder, suggests that maturing may just mean accepting that no one lives exactly as they plan, and yet there is something profoundly liberating about continuing to insist.

Film:

He Died With a Falafel in His Hand

Director:

Richard Lowenstein

Also:

2001

Gender:

Comedy/Romance

Assessment:

9/10

1

1

Helena Oliveira

★★★★★★★★★★

Hi! I’m Renato Lopes, an electric vehicle enthusiast and the creator of this blog dedicated to the future of clean, smart, and sustainable mobility. My mission is to share accurate information, honest reviews, and practical tips about electric cars—from new EV releases and battery innovations to charging solutions and green driving habits. Whether you’re an EV owner, a curious reader, or someone planning to make the switch, this space was made for you.

Post Comment